I’ve been on two Epic Journeys recently. The first, which I’m not yet ready to write about, was the journey through leukaemia with my partner and soulmate, Dave. It ended with him dying, in June 2019.

This blog is about my second journey, fulfilling a lifelong dream to travel overland to Asia and helping me square the circle of wanting to visit family living in Thailand without flying there and back. Because climate emergency. It’s not just me, there’s a whole No-Fly Movement now and it’s making travel adventurous and romantic again!

Yorkshire to a Thai Island, Overland

21 December, Winter Solstice

Yorkshire to London

22 December

London to Vienna, Austria

The folks in charge of Vienna let coca-cola put massive banners on the screened scaffolding around the gothic cathedral in Stephansplatz, in the centre of the city. Somewhat spoiling the charm of Christmas markets and horsedrawn carriage rides. Beneath the coke ads I eat potato fritter with sour cream washed down with a mug of bio-gluhwein.

For twenty hours, from London to Prague, I’m seated next to an annoying smelly man. I make the transfer in Prague with just two minutes to spare, after the Czech polizei drag a guy off the bus at the border and we wait until they let him back on.

23 December

Vienna to Kiev, Ukraine

Snail train through Ukraine in the rain. A tiny 3-berth compartment, bunks stacked on top of each other with barely space to turn around alongside them and a ladder that only reaches partway to the ground from my top bunk which is terribly close to the ceiling. My cabin mates aren’t great at co-operation.

Kiev

I have two hours to change some cash, buy water and tea and fruit, rehydrate, find the ticket office, swap my Polrail confirmation slip for a printed ticket, and find my train.

Everything seems very strange, uniformed men are herding people out of the station, the area directly in front is cordoned off, and I can’t work out how or where to do the things I need to do. I have a headache. The people I approach for help don’t speak any English and seem pretty cross. Finally a guard with a twinkle in his eye and a smattering of English explains there’s a bomb scare. He gestures towards another nearby station where I can get my ticket, and across the road to a money exchange place. He can’t tell me whether my train is likely to leave on time, or at all.

After 90 or so fraught minutes I’ve done all the things and after a few false leads have even found the platform my train will leave from. The bomb scare, if it’s still on, isn’t affecting this part of the station. I board; this is a better train, bunks only two-up and all open plan – no compartments, so no claustrophobia.

As we pull out of Kiev, I’m welcomed like a long-lost exotic sister by Peter, a 60 year old Kazakh philosopher, and Sergei, a young Russian geek; both are keen to practice their English and discover what an English woman is doing on their train. When I explain to the Kazakh I’m travelling overland because flying is bad for the environment he says “Ah! The Swedish girl!” He got his start learning English by listening to The Beatles and Rolling Stones as a youth, and believes doing things that are hard makes you stronger.

The border guards here have guns and dogs.

24 December, Christmas Eve

Moscow

The metro is confusing. Also palatial, ornate, and lit by chandeliers. Russians so far seem friendly; a young guy notices my perplexity and sets me going in the right direction for Yaroslavskaya Railway Station, where I stash my rucksack in the baggage store. The Information Point staff don’t speak English and are under the impression that if they speak Russian loudly and slowly enough, I’ll understand.

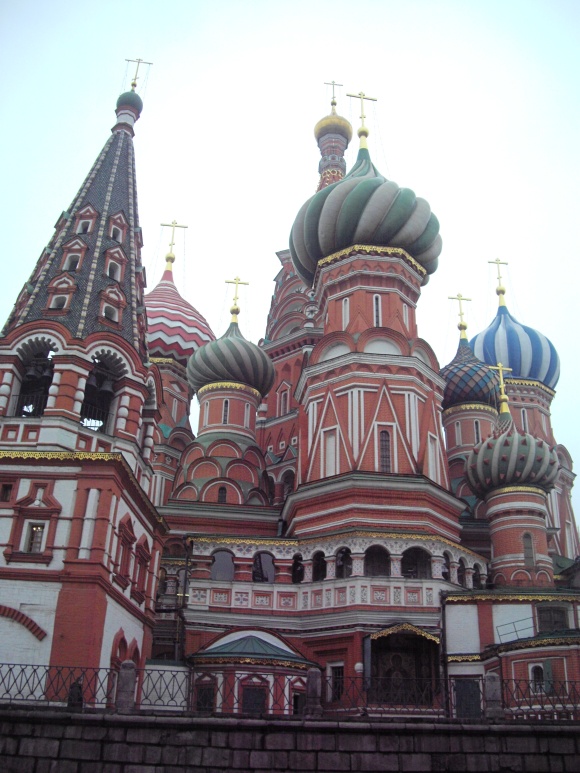

Back into the metro system to Red Square and St Basil’s Cathedral, Zaradye Park, the Kremlin, a Stalin-era skyscraper and a whole chain of gorgeously decorated sparkling winter gardens and Christmas markets. After six hours in the city I’ve stopped feeling like a scared rabbit, I’m smiling and I’ve managed to buy a hot chocolate and cherry pastry. Then it’s back to Yaroslavskaya for Russian salad and yogurt and to gorge on a fat Stephen King novel while waiting for my 11.45pm Trans-Siberian Express, hoping reality lives up to the romance of my imagination.

I have a 4-berth compartment to myself. I’m in a top berth, there’s plenty of head room, hooks and rails to hang things from, and a big luggage store at the foot of the bed. I make up my bunk with clean white sheets and coarse wool blankets, use surgical tape to stick Christmas cards to the wall, and toast the epic journey with a swig of fine brandy from Dave’s hipflask as the clock passes midnight on Christmas Eve, then I sleep.

25 December, Christmas Day

Trans-Mongolian Express, through Siberia

Christmas Day. It’s snowing.

Every sleeper train seems to be designed slightly differently but each of the last three has been carpeted with blue or red patterned rugs. This one is dirtier and shabbier than I expected, with harder bunks and is lacking a shower, but there’s space to partially unpack and to sit at a table observing Russia go by. I’m alone, peaceful, smiling, quietly excited. Outside, silver birch and fir trees. A wide frozen river. A 1960’s car.

At the end of the corridor, a stove with back boiler heats the carriages and provides free hot water in an urn for tea and soup and couscous.

Through the window I see small houses with steep pitched roofs, slightly bigger houses with roofs shaped like old-fashioned canvas house tents. It’s icy underfoot; I see people sliding as they walk.

Down the corridor, Chinese train guards squabble and steam wonton. The world outside is monochrome, a black-and-white landscape with peach-pink backdrop. As the sun sets over Siberia I have a slice of mum’s miniature Christmas cake washed down with brandy and breathe deeply. For two years, while Dave was ill, I rarely breathed deeply; was always holding my breath in hope. Ever since he was diagnosed with leukaemia in December 2017, my primary concern was him. Now, I miss him and whisper to him, feel as though I’m doing this journey for him too, but I’m also free to breathe and spend the day reading and relaxing. I’m on holiday!

The dining car is cleaner and newer than the sleeping carriages. It’s almost empty. There’s a small Christmas tree in the bar, tinsel and baubles at the windows. I treat myself to a Christmas dinner of fried potatoes with mushrooms.

26 December

Trans-Mongolian Express, through Siberia

I think of the book and film The Long Walk, of prisoners escaping a Siberian prison and walking to safety, through forests and deserts, to India. I think of permafrost, of climate change melting permafrost and gases bubbling up, long-frozen bodies rising up and decomposing. I think of Communism stretching right across Russia to China, heading down into Asia and jumping across oceans to parts of South America. Vast territories. I wonder how and why it grew so big and went so wrong.

A billion Christmas trees outside my window, boughs laden with snow. The snow is deeper now. Big flakes are falling. At stations people pull their luggage along the platforms on sledges. At Ishim we stop for 10 minutes, time enough to wrap up and climb out, to trample in the snow. There’s little to see: bundled up passengers, turquoise station buildings, grey-white sky, snow, guards wearing furry hats with earflaps turned up and pinned on top, drab buildings in the background.

Later, as we pass through another station at dusk, the clock reads 4.55pm, three hours later than I thought. We’ve been passing through time-zones, unannounced and un-noticed. Cars, trucks and buses make their way along iced roads.

My carriage is mostly empty, save one quiet Japanese passenger, occupying his time with books and simple food, like me. We smile, cautiously. I’m in no hurry for company.

27 December

Trans-Mongolian Express, through Siberia

Sunshine on snow. I can feel the warmth of the sun, faintly, through the double-glazed window which today has ice crystals between its panes. The fir trees are big to the north, where the land undulates gently. Elsewhere skinny silver birch shimmer under a sky of pale, snow-washed blue. In larger settlements there are a few big, brick-built houses but mostly the dwellings are of wood, small cabins with chimneys; some are painted bright turquoise or pink, or yellow, or blue and green; I want to live in one. Many have garden plots and greenhouses, all snow-covered now but ready for spring cultivation.

Krasnoyarsk is a big city. Mile after mile of scattered cabins give way to denser housing, factories and warehouses, mean tower blocks, cranes, HGVs, apartments, industrial chimney stacks. Traffic lights, petrol stations, graffiti on railway hoardings. Ordinary urban things out here in Siberia. On the platform cold stings my cheeks, makes my eyes water, takes my breath away. It’s minus 21 degrees. The train guards take up tools and chip away the ice from our undercarriage. I jump back on board, skin tingling, eyes streaming, invigorated, glad I don’t have to be out there for long. There’s a sharp breeze blowing fine snow-dust. It looks like glitter streaming past the window as we pick up speed. There are snow ploughs on the roads, coal-laden cargo trains on the tracks. Rose-gold snow in late afternoon sunlight.

I eat well with the aid of the hot water samovar: oats with raisins and sunflower seeds and honey for breakfast, miso soup and oatcakes for lunch, spiced-veg couscous with rehydrated seaweed for dinner. Tea and Christmas cake mid-afternoon. Hot chocolate with brandy before bed.

We’ve gained another couple of hours. I’m experiencing jetlag in slow motion.

28 December

Trans-Mongolian Express, Irkutsk to the Mongolian border

At 7.30am I’m woken from a deep sleep by the arrival of three Australians in my compartment. They’ve just embarked, in Irkutsk. They are loud, and take up a lot of space. We have introductory conversation consisting of who, where, when and why? I explain that my dad and sister are in Thailand, an overland journey to Asia is a long-held dream, and I don’t want to fly for environmental reasons.

“Ah, climate change!” exclaims Viv. “We’ve travelled through South America and Europe, and everywhere we go people tell us how their place has been affected. Glaciers retreating. Landscapes changing. Wildlife disappearing. From Peru to Sweden, and now you!”

The Aussies crash out after strewing their belongings around and parking an enormous suitcase in the centre of the compartment. My palace suddenly feels extraordinarily cramped. I dress on my bunk, make a mug of sweet coffee, use one of the fold-down seats in the corridor to drink it, then head to the dining car. The unheated ante-chambers between carriages are deep freezes, choked with snow. I choose toast-with-jam from the menu, it has the taste and texture of eggy bread; I like it. The dining car is way too warm, over-heated and stuffy, so I escape back to the corridor.

Irkutsk! I’m in a game of Risk.

My corridor seat is perfectly placed for viewing Lake Baikal, the deepest freshwater lake in the world. It stretches on and on, and on and on. Every so often we reach a promontory and I think it’s the end of the lake, but no, we pass through a tunnel or top a rise, and there the lake is again. It’s mostly water, choppy in places, mist rising from it in others, with some frozen sections, ice on ripples, miniature icebergs along its bank. It doesn’t freeze over until January. Ellie Weirdigan walked across Lake Baikal, camping on the groaning ice, a couple of years ago. A fisherman strides by, well-muffled. A small blue car speeds along an icy lane. Horses graze on frozen clumps of coarse grass poking through snow.

In the afternoon I meet Dave, semi-retired John Lewis manager, and Jayne, primary school teacher. They pass along my corridor between the dining car and their first-class carriage. They have a twin berth compartment, in fake mahogany, with a shower that doesn’t work, and red rather than blue carpets. Their beds are soft. It’s Dave’s 60th birthday in a couple of days; he lends me his Trans-Siberian Trailblazer handbook and invites me to join them for birthday cake on the 30th.

We arrive in Naushki, the Russian border town, sometime around midnight. Border guards and customs officials board the train, wake us, demand passports, order us out of bed, give us forms to fill, study our visas then let us sleep again. An hour or so later we’re at the Mongolian border town of Suhbaatar and it all happens again, through a haze of sleep.

29 December

Trans-Mongolian Express

I wake up in Mongolia. Mongolia! That place I decided I must visit 27 years ago while watching a surreal film in a Sydney arthouse cinema featuring Mongolian nomads galloping across the steppes and living in round tents called gers (the surreal bit involved a tv and satellite dish with nowhere to plug it in).

Low, snow-covered hills, bright sun in a blue sky. A scattering of small houses in the valley through which the rail tracks run. Where the buildings are painted they’re mostly red, white and green. Each house surrounded by a fence enclosing a rectangular piece of land. In some plots, gers sit in front of the buildings with smoke rising from chimneys. The herdsfolk are off the steppes for winter but still living in their traditional, well-insulated yurt-homes. Just once, a circle of gers on the edge of a settlement, away from the bricks and fences.

We pass small farmsteads. Snow-covered haystacks. Big dogs with thick fluffy coats. Horses. Cattle. People, bundled in hoods, headscarves and long coats, unloading coal from an open-topped wagon. There are vast coal reserves beneath Mongolia along with other valuable resources to be mined; Russia and China are moving in.

In Ulaanbaatar, capital of Mongolia, I wave goodbye to the Aussies and the Japanese guy. There’s time enough in the station to walk along the platform. My nose hairs freeze, a peculiar sensation. Dave and Jayne dart around the station building, taking photos from all angles while I chat with Dean, from Cardiff. He’s also heading for Thailand, armed with a recently acquired TEFL certificate and no need to return. Back on the train I realise the Australians must’ve scooped up my super-comfortable sandals with their belongings. They’re long gone. A pair of fake-fur-lined snow boots is now my only footwear. Fine until I get to the tropics.

I spend an hour or so pining for my sandals then meet Dave and Jayne in the Mongolian dining car which was joined to the train at the border, the Russian restaurant returning to Moscow. It’s a gloriously ornate carriage, with carved wood and golden tablecloths, and it’s full. Lots of people embarked in Ulaanbaatar – people from Canada, Ireland, Scotland, Italy and Germany as well as Mongolians – joining the English, Welsh, Chinese and Swedish travellers already aboard. Jayne has brought along a fruitcake for Dave’s 60th, a Waitrose Christmas cake posing as birthday cake. Dave slices it into crumbly lumps, offers it around on serviettes begged from the dining car attendants. Jayne whips everyone up to sing Happy Birthday, and then because the beers are flowing we have Happy Birthday in Swedish, German, Italian and Glaswegian too.

From the train tracks Ulaanbaatar was an ugly blot of grey and beige concrete and towerblocks on a pristine white plain. Beyond, there are herds of ponies. Wild, or just roaming free until needed? We’re skimming the Gobi Desert and the landscape’s flatter, emptier. I’m beginning to think this bit of the journey isn’t long enough. I could live on this train for a few more days, easily.

There are flocks of small birds, the occasional larger bird of prey. Silhouettes in flight as the sun sinks. A gazelle, leaping through snow. Then, a whole herd of gazelles and a new moon rising, Venus clear beside it, in a violet sky over an apricot horizon.

After dark, I return to the dining car at Dave and Jayne’s insistence, to share in a bottle of pink fizz. It’s been chilling between the carriages. I eat omelette, the only vegetarian dish on the menu. They eat goulash. Dave orders a second bottle of pink fizz and the whole dining car toasts him again.

30 December

Trans-Mongolian Express, through China

We reach Erlyan on the Chinese border about 1am. We have to disembark to go through passport control and customs. One border policewoman has long false nails painted sparkling silver. Once all passengers are back on board the train is shunted into a huge shed for bogie-changing. The tracks in China are of a different gauge so the wheels have to be de-iced, taken off and replaced. This involves lots of banging and shaking. I try to doze through it. We cross into China around 5am and I sleep until 9.

In China there’s only a light dusting of snow but it’s still very cold. The landscape is mostly pale brown under a blue sky. A Mongolian guy tries to fight the Chinese train guard; his family pulls him back into their compartment. At train stations in Russia and Mongolia the guards disembarked and stood in clusters, casually chatting, or bashed ice from the undercarriage wearing furry hats and bomber jackets over their simple, indoor, blue cotton uniforms. In China they don smart greatcoats with golden badges and shoulder insignia, wear peaked caps with gold braid, and stand to attention at the doors. They’re the same guys though. The main guard in my carriage has become friendly towards me, thawing gradually over the six days we’ve been travelling, smiling occasionally now and trying out the odd word of English. I ask him to teach me the Chinese for thankyou: “shjee-ah-shja” I try, and he nods.

Now there are solar farms and wind turbines, tree nurseries, reforestation. And then, the Great Wall of China, climbing hills a few kilometres away, looking just like it does in pictures. I doze, wake to fluted and jagged mountains above an iced-over lake, then a dam and deep river valley. The river is frozen, criss-crossed with bridges, lined with trees. Sunlight hits the peaks above, turning them amber and gold. Everything below is tones of grey and brown and white, but not dull. I wish I could paint this scenery, it’s subtly gorgeous.

All passengers have been given tickets for a free lunch in the new Chinese dining car which joined us in Erlyan. This is the most drab dining car of the three, and by far the coldest. There’s no menu, no choice. For vegetarians it’s steamed veg and rice. For meat-eaters the same plus meatballs. All the Westerners are crammed together on four tables. We discover there are four teachers and a surgeon amongst us. After lunch I chat with Dean, tell him about Dave dying. His best friend died of leukaemia three years ago.

I want to explore more: Mongolia in summer; the Silk Road through Kazakhstan, Kyrzgistan, Uzbekistan; I want to go from Thailand through Myanmar to India and Pakistan and Iran (probably a wish too far); I want to visit Kurdish Awraman; make my way back through Turkey. When I started this journey I wasn’t sure the travel-magic would work. Seems it is.

Now we’re heading into the outskirts of Beijing. Street lights, neon, billboards, tower blocks, wide highways, urban sprawl. Ejected into the capital of China as night falls. There’s no snow but it’s minus 20 degrees, bitingly cold. I’m lost, but a fellow traveller points towards the subway. Leo Hostel sent directions by email, I have them here printed out, they take me to Qianmen Square where I lose my way and walk around, cheeks stinging, nostrils freezing. Eventually get my bearings, follow my map past ornately tiled shopfronts with red lanterns, past Beijing Hutong Duck restaurants, along narrow streets where all the signs are in Chinese, where there are no cars but dozens of two-and-three-wheeled vehicles from bicycles to mopeds, scooters, auto rickshaws, cycle rickshaws and hybrid versions. The drivers and cyclists wear thick padded glove-and-cloak combinations, like open sleeping bags with arms. Many of the mopeds are electric and make no sound as they approach.

I find Leo Hostel, fall into my bunk and sleep.

31 December, New Year’s Eve

Beijing

I go through security checks to enter Tianamen Square and again to visit the Forbidden City. I spend too long looking at the least interesting things and have to rush the best bits. There’s military pomp – soldiers in pristine uniforms standing to attention on platforms in front of statues. There are palaces that look like temples and outbuildings that look like palaces; terracotta tiled roofs, frozen moats, marble bridges, ancient trees and grottoes; a museum of Buddha statues, jars and vases, paintings and other artefacts; a walk along the wall around the Forbidden City with views across Beijing; trinket shops and a rare cafe with menu in English. I eat rice with egg and tomato washed down with sweet, fragrant milk-tea.

As the sun sets everyone’s hustled out of the Forbidden City by the north gate and I’m miles from Leo Hostel. I explore further, making it to the Drum Tower and Bell Tower and the nearby waterfront hutongs (alleyways crammed with streetfood and trinket shops). I can’t face deciphering public transport so walk back to the hostel, must’ve walked 15 miles or more today, my knees are cold and though it’s New Year’s Eve it’s not Chinese New Year, so I fall into bed with hot chocolate and a book just before midnight.

I miss Dave. I still can’t believe he died.

I sleep, and am woken periodically by Happy New Year texts from friends in other parts of the world.

January 1, New Year’s Day

Beijing, and towards Nanning, China

Milk tea and custard pastry from the corner of my street for breakfast. A stroll around the hostel’s neighbourhood, buying fruit and roasted broad beans for the onward journey, then by subway to Beijing West Railway Station. I’m starting to get the hang of things; I find my way, get on the train to Nanning. I’m in ‘hard sleeper’ class, which means six cramped bunks to a compartment. I’m sharing with a rowdy family from the countryside and a chemistry professor. The family speak no English so the professor complains to me about their behaviour. He also complains about the Chinese government, Muslims, America, the internet and smartphones. He’s slightly miserable, but quite personable.

It’s raining. The compartment’s too hot. But I sleep, some.

January 2

To Nanning, and onwards towards Hanoi, Vietnam

The landscape is limestone karst today. Dozens – hundreds – of striped-rock, green-clad hills. Below them, patchworks of cultivation, irrigated paddies, duck farms with free range birds around muddy pools, banana groves, corn stalks and palm trees.

At Nanning I have to change train. It’s much warmer than I expected, and humid. The station is teeming inside and out, there are people milling and sitting on steps and pavements and hall floors: city people in smart clothes with wheeled suitcases; countryfolk sitting on sacks and upturned buckets. There’s a hubbub of conversation. Everyone’s more animated here, away from the Beijing cold; it’s beginning to feel like South East Asia. The locals are wearing coats, but I’m down to a t-shirt.

I spend the last of my yuan on bananas, oranges, dried mango and iced green tea. The tea reminds me of Bangkok, and of Dave.

I’ve somehow ended up in ‘soft sleeper’ class for the Nanning to Hanoi leg of the journey. The bunks don’t feel any softer but there are only four of them to a compartment and the furnishings are frightening. A shiny white mattress is covered with a white sheet, on top of which sits a white quilt and two white pillows. There’s a table with white damask tablecloth, white lace curtains, a white lace antimacassar on the shiny white back rest, which matches the plump white satin coathanger. I feel grimy. Very, very grimy.

January 3

Hanoi, Vietnam

I follow an old hand, a French guy doing a visa run from China, to a public bus which takes us 6km for 10p. There’s a lake near the Old Quarter in Hanoi, Hoan Kiem Lake, an oasis in the heaving hooting city; I head for it, wander about, find a cheap room five flights up in a back alley guesthouse. I learn how to cross roads. It’s an art-form. No hesitation, no stopping, no running, don’t trust the traffic lights, don’t expect vehicles to obey rules, but don’t worry, no one wants to hit you. Then I buy a bus ticket and a new power adaptor. That might not sound very eventful but everything’s challenging and exhilarating the first day in a new country.

It’s warm. Not hot, but t-shirt weather. I try to go to the Women’s Museum – “this excellent museum focuses on women’s role in Vietnamese society and culture, with objects superbly laid out and labelled in English and French – from wartime propaganda posters to tribal artefacts…” – but where it is supposed to be there’s a Starbucks instead. On my way back to the lake I find this cathedral with nativity scene outside.

Evening. I’m still wearing snow boots, head to the night market to find a pair of flipflops. I learn how to buy food, then discover a swathe of blocked off road with music blasting and people dancing. Not just dancing but proper dancing – waltzes, flamenco, rumba, all kinds of intricate partner dancing. An audience is gathering as I arrive, I join it and spend the next hour completely rapt. Women are thrown in the air and caught before they land on their heads on the tarmac. Some couples dance exquisitely, some clumsily, one couple argues, one bloke is very bossy; it’s a soap opera in dance. What a fabulous thing to stumble across.

Armed with a new power adaptor and now in a land of wifi, I catch up on world news. The Middle East is in uproar because Trump, and Australia’s on fire. People in the media don’t seem to be talking much about tipping points and runaway climate change but vast, vast areas of forest going up in smoke and flame looks like it to me. Meanwhile Jakarta, just a hop away from Aus, has had the worst floods in living memory and they’re talking about moving the capital of Indonesia to a different island, permanently, because Jakarta will be under water soon.

January 4

Hanoi to the Laotian border

Hoan Kiem lake is the heart of this part of the city, or perhaps the lungs. Hanoi has visible air pollution, lots of face masks. People come to the lake to sit amongst greenery, doze on benches in the afternoon, practise Tai Chi at dawn. In the surrounding side streets people squat on tiny low stools around miniature braziers, brewing and drinking tea, cooking up noodle soup, taking lunch breaks on the crumpled pavement.

I find a Vietnamese coffee house for breakfast (remarkable coffee, rich and sweet and strong, like dark chocolate) and a cheese baguette (French colonial legacy), then walk a couple of kilometres to the Temple of Literature, a complex of curly-roofed buildings, ornamental gardens and statues dedicated to learning and contemplation.

Then to the bus station, to begin my 20-hour bus journey to Vientiane.

As midnight approaches, the roads grow quieter and narrower and the bus climbs towards the border – then breaks down. I disembark to see what’s happening. We’re on a steep, rough road through humid, forested mountains. The driver and his mate are jacking up the bus. One of them crawls underneath. Most passengers are still on the bus, sleeping. A part needs changing. I’m roped in to help (unskilled assistance – holding up a flap of metal). Two hours later it’s all done and we set off again, reaching the border at dawn. Mist rises from a steaming jungle. The roadsides are strewn with plastic rubbish.

January 5

To Vientiane, Laos

Stunning landscapes. Limestone karst, mountains all knobbly and jagged, lush vegetation, green rivers.

Vientiane is a small city, a lazy slow relaxed city full of temples and restaurants. I miss Dave, do some laundry, eat egg fried rice, retire early to a rather posh room that excited me on arrival but on closer examination lacks character.

January 6

Vientiane to Nong Khai, Thailand

Across the Friendship Bridge. Over the Mekong River. Into Thailand.

I’ve dreamed of making this journey for 30 years.

In Nong Khai I grab the last cheap room in a gorgeous guesthouse in gardens next to the Mekong.

Nong Khai has a lovely wide promenade beside the river, great for strolling except my replacement flipflops have given me blisters, hampering my yomping about.

I catch up on emails in my room, beneath a lazy fan. It’s hot here.

January 7

Nong Khai, and on to Bangkok

I hire a bicycle. Visit Salakaewdoo, a surreal sculpture park created by Leua, a Laotian mystic, in the 70’s and 80’s. Giant Buddhas, Hindu gods and goddesses, demons and humans and animals sculpted from concrete, some towering eight stories high. Immense! Unbelievably huge!

In the Wheel of Life enclosure I light a stick of incense and have a revelation.

I can stop saying sorry to Dave for all the things I did less than perfectly in our relationship. He doesn’t mind anymore, he’s moved on, he’s beyond being annoyed with me. I’m forgiven. I can still love him, but I don’t have to be sorry.

Cycling back to my guesthouse I stop at the market and find a pair of comfortable sandals.

Then it’s an overnight train to Bangkok.

January 8

Bangkok and beyond

A 14 hour bus journey and I’m on a southern Thai island with my family, being treated to delicious fresh food.

The Epic Journey is complete.

I highly recommend The Man in Seat 61 for advice on overland travel: https://www.seat61.com/